Vernon L. Williams

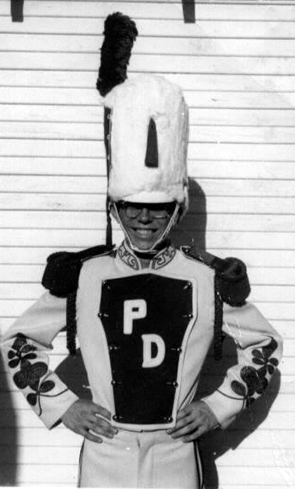

BeginningsI grew up in an Air Force family during the 1940s and 1950s. My father, M/SGT Andrew L. Williams, served first in the Army Air Corps in 1942 and later retired from the U.S. Air Force in 1964 at Amarillo Air Force Base during our junior year at Palo Duro. During World War II my father served in the Pacific war with the 509th Composite Group, the unit that flew the two atomic bomb missions from Tinian Island in 1945. He was responsible for the modifications to the bomb bay of the Enola Gay, the B-29 aircraft assigned the first atomic mission to Hiroshima. Later he named my sister after the famed aircraft, Enola Gay Williams Boyd, also a graduate of Palo Duro in the Class of 1975. Interestingly, in recent years Enola Gay has worked for Boeing Aircraft, the very firm that manufactured the B-29 bearing her name. During the years growing up, I traveled with my family while my father served in assignments in England, Bermuda, Okinawa, Amarillo AFB, Westover AFB before returning to Amarillo AFB where he retired just before the base closed in 1964.Palo Duro YearsDuring my years at Palo Duro High School, I played in the band and orchestra, but was not a serious student. This is almost humorous now because of what I have become, and what I have been doing as a career for the last three decades. More on that later.During our senior year, I was the head drum major for the band and played French horn in both band and orchestra. Both Joel Shackelford and I came over from Horace Mann Junior High as cornet players, but Mr. Bledsoe convinced us to switch to French horn during the middle of our sophomore year. That decision changed the course of my early adult life later on and it enriched my life during my remaining years at PD. French horn players received some special opportunities in the music we played, and it also offered me a chance to play in the orchestra. George Bledsoe became a mentor to me and remains an inspiration to me in everything I do. I am grateful to have known him in old age and be there at his funeral to tell others of his message of excellence during his teaching career, and the impact that he had on his students. Two months before he died, his Palo Duro students--representing all thirteen years of his Palo Duro service (1955-1968) -- brought him back to Amarillo for a special tribute weekend honoring him (see more about the Bledsoe Tribute Weekend in the band section of our website). I am so thankful that we did that for him before it was too late. Joel was my best friend, and he soon became more of a brother to me. When my father retired from the Air Force in 1964, we moved back to Brevard, North Carolina where I was born. As an Air Force family, we had traveled the world but had never really lived in Brevard--only vacation visits to grandparents every so often. I missed Palo Duro and my friends and finally talked my parents into letting me return to Amarillo on my own. I would never have let my own young son do that at age 17! I left Brevard, hitch hiking back to Texas with $1.26 in my pocket. There were some middle-of-the night, difficult times, but I made it back to Amarillo in about a week, thanks to some new friends along the way. Soon I was standing in Mr. Bledsoe's office, explaining that I was back. It proved not to be as simple as that. What I did not understand was that families who lived in Amarillo were tax payers which funded their children in the Amarillo Public Schools. The family's home location determined what schools that their children would attend. I had no family in Amarillo, no family home, no tax paying parents. They were in North Carolina. I was living with church friends and soon, I would go to live with Joel and his parents. Anyway Mr. Bledsoe called the principal, Windy Nicholas down to the band hall, and the three of us met in Mr. Bledsoe's office. Mr. Nicholas asked me why I was back in Amarillo and at Palo Duro? I desperately explained how much that I missed my friends and going to Palo Duro. I described the journey that I had made from North Carolina and a dangerous encounter that I had at 3 am on the outskirts of Nashville and how other more sympathetic Good Samaritans bought me meals when I had no money, and the trucker who allowed me to sleep in his cab as he drove across western Tenneesee and on into Arkansas. I told Mr. Nicholas that it was all worth it, and that I would do it again. I was convinced that my future, whatever it would prove to be, was tied to Palo Duro High School, the teachers there, and my classmates whom I saw as family. Mr. Nicholas just looked at me and said nothing, thinking about what I had said. I can't imagine what he was thinking about the bizarre story that I had just told him. Eventually he aaid that I could stay and that he would take care of everything, that I was not to worry. Nothing was ever said again to me about my status at Palo Duro High School. I remained there until I graduated on May 28, 1965. I never found out what he did to make my enrollment legal or acceptable to the Administration. And of course, all that followed in my life, graduate degrees, scholarship, and the academic and commercial successes, I trace back to that moment in the band office where Mr. Bledsoe and Mr. Nicholas bent the rules to let me stay and allow me to build a foundation for my future. Playing in Army Bands During the Cold War

The weeks after graduating from Palo Duro, I joined the Army on June 22, 1965--just three weeks after graduating from high school. Knowing that the draft was looming for all of us guys, I had joined the Naval Reserve earlier during my junior year.

I went to an excellerated basic training at Treasure Island in California and later more training aboard the destroyer escort Williard Keith at Norfolk, Virginia. I found out that I had

a serious problem with sea sickness so I talked to George Bledsoe about helping me get into an Army Band. George had gone to the University of Texas with Army Bandmaster Herbert J. Bilhartz

after World War II and were good friends. At the time Bilhartz was in command of the 62nd Army Band at Fort Bliss in El Paso, and he agreed, based on George Bledsoe's recommendation, to

send me an official audition letter with a score of 92. I did not know it at the time, but that high score allowed me to go directly from basic training to the band in El Paso. Other new bandsmen had to go

to the Army/Navy School of Music first, but I did not. Another part of my good fortune was that Bilhartz was a French horn player, so I received free horn lessons from him during my year in the 62nd.

He also appointed me the drum major of the band so I am assuming Bledsoe had told Bilhartz about my year as head drum major at Palo Duro. Here is a clip from the film Eighth Army Band: A Clash of Cultures where I talked about my beginnings as

an Army bandsman. |